Is There Such a Thing as Too Much Consent in Student Coaching?

Every once in a while, a question gets asked in our Anti-Boring Learning Lab that makes me slow down and think a little more carefully.

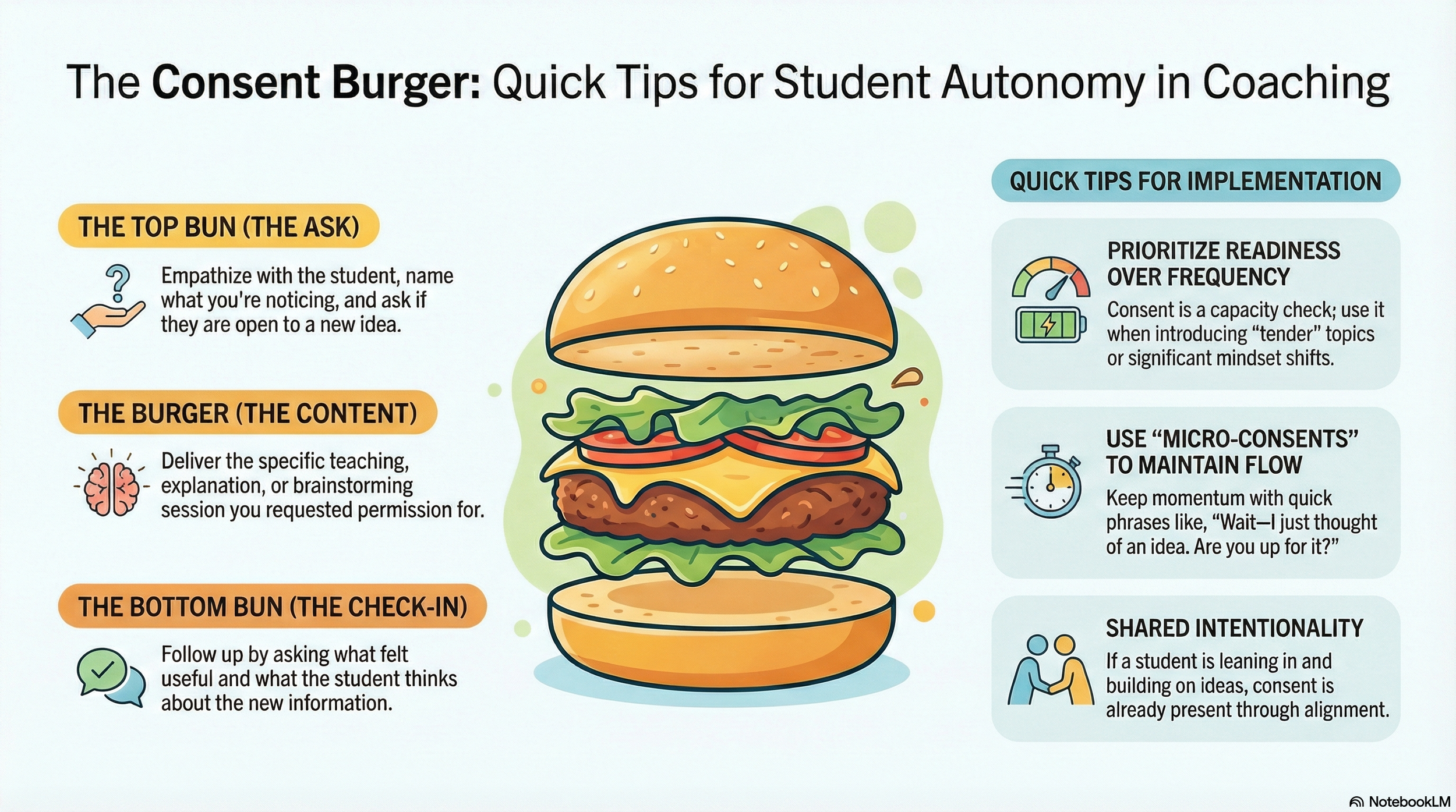

This one came at the end of our Academic Coaching 101 module, where we explore the difference between teaching and coaching, how to ask empowering questions, and how to use a framework I call the Consent Burger. In her end-of-module reflections, one academic coach asked:

“How often should we be requesting a student’s willingness to participate in learning a new skill? Is it once before every session or, if multiple skills are being taught, is it best before each one? Just wondering if one strategy has worked better than others.”

It’s a thoughtful question—one that shows real respect for consent as a coaching tool. It doesn’t have a neat, formulaic answer, but it’s well worth unpacking.

Before answering it directly, it helps to make sure we’re working from the same definition.

What the Consent Burger Is (and Why It Exists)

I created the Consent Burger to be a communication framework used in academic coaching and executive function coaching to help students feel respected, involved, and agentic—especially when a coach wants to introduce a new skill, strategy, or way of thinking.

Many coaches feel a tension here. Those coming from classroom teaching often err on the side of over-teaching or lecturing, even when students aren’t fully ready or engaged. Coaches trained in life coaching spaces sometimes err in the opposite direction, holding back useful instruction in an effort to stay non-directive.

The Consent Burger exists to bridge that gap. It offers a way to teach without taking over, and to share expertise while still honoring student choice.

At its core, it has three parts:

Top bun: empathizing with the student, naming what you’re noticing, offering context, and asking whether they’re open to learning or exploring something

The burger: the teaching, explanation, conversation, or brainstorming you said you’d offer

Bottom bun: checking in afterward to ask what felt useful, what didn’t, and what the student thinks

A coaching example might sound like this:

“I’m noticing that this assignment keeps getting stuck at the planning stage, and I have an idea that might help. Would you be open to hearing a bit of brain science that could explain why this keeps happening? I think it would take about ten minutes, and then we can decide together whether it feels useful and what to do next.”

That opening context is the top bun.

The content you promised is the burger.

And the check-in afterward—“What do you think?”—is the bottom bun.

That’s the structure.

Reframing the Question: From “How Often?” to “When?”

On the surface, this sounds like a question about frequency. How many times should we ask for consent in a session?

Underneath it, though, is a different concern: how do we know when a student is actually ready to engage?

Research on motivation and learning consistently shows that autonomy matters. Self-Determination Theory, for example, tells us that students are more engaged and persistent when they experience choice, relevance, and respect—not pressure or compliance.

Seen this way, consent isn’t a ritual to perform once (or repeatedly). It’s a way of staying attuned to readiness.

Consent as a Capacity Check

Readiness isn’t static. A student can walk into a session generally willing to work—and still lack the nervous system capacity for a specific task in a specific moment.

Stress, fatigue, threat, or past experiences of failure all reduce access to executive function. Cognitive load theory reminds us that working memory is limited; when students are overwhelmed, even well-designed strategies won’t land.

From this lens, asking for consent is partially a reflection about capacity. It’s a way of checking whether the student can actually use what you’re about to offer.

That’s why consent sometimes needs to be revisited within a session—and sometimes doesn’t.

When Asking for Consent Is Most Useful

Explicit consent is especially useful when you’re about to introduce something that could meaningfully shift how a student understands their learning.

That might be a new strategy, a new way of thinking, or an observation that asks the student to look at themselves differently.

For example, imagine you’re working with a student who says they “study for hours,” but their grades don’t reflect that effort. Over time, you’ve noticed that most of their study time is spent rereading notes and highlighting—strategies that feel productive but aren’t very effective.

You might want to introduce retrieval practice. But you also know this student takes pride in how hard they work, and that suggesting a change could easily land as “you’ve been doing it wrong.”

That’s a moment where consent matters.

Instead of launching straight into the science, you might pause and say:

“Can I share something I’ve noticed about how studying tends to work for most brains? It might challenge some of what you’ve been taught, so I want to check first whether you’re open to hearing it.”

That check-in does important work. It signals respect, prepares the student for a possible mindset shift, and gives them agency in how the conversation unfolds.

In moments like these, asking for consent isn’t about slowing things down. It’s about creating the conditions for learning to actually land.

When Asking for Consent Feels Clunky

So let’s come back to the original question: do you have to ask for consent every single time you introduce something new?

Not necessarily.

If you find yourself asking “Are you willing?” every time a new idea crosses your mind, consent can start to feel clunky. If the Consent Burger becomes a sequence you feel required to rinse and repeat every time you open your mouth, that can be too much.

At that point, it risks feeling stiff or unnatural. It may even feel mildly annoying, as if every interaction requires formal permission before anything can happen.

At the same time, skipping consent altogether—especially when you’re introducing a new direction, naming something sensitive, or noticing a shift in energy—can quietly pull students back into a familiar dynamic where adults decide what happens next.

The Consent Burger isn’t meant to be used mechanically. It’s a structure that helps you notice when a moment actually calls for consent, and when alignment is already present.

Often, the more useful question isn’t “Have I asked for consent recently enough?” but “Are we still moving forward together?”

When Consent Is Already Present

Consent isn’t only communicated through words. Often, it’s already present in the structure of the interaction itself.

When a student has agreed on a goal for the session, is actively engaged, and is building on ideas with you, there’s usually a shared sense of direction. Learning science sometimes describes this as shared intentionality—both people oriented toward the same purpose.

From an autonomy perspective, this matters. Students don’t need to re-approve every step as long as they experience choice, relevance, and respect within the work. Once alignment is established, consent is maintained through responsiveness, not repetition.

There’s also a cognitive load consideration. When students are focused and engaged, unnecessary meta-checks can interrupt flow without adding clarity.

Practically speaking, if a student is leaning in, asking questions, or extending the work, consent is usually already there. A light check-in—“Want to keep going?”—is often enough.

Consent Doesn’t Always Need the Full Burger

One reason coaches worry about asking for consent “too often” is the assumption that consent always has to look like the full Consent Burger.

In reality, once trust and alignment are established, consent often shows up in much smaller ways—micro-consents that keep students oriented without slowing things down.

These might sound like:

“Wait—I just thought of a new idea. Are you up for it?”

“Can I pause us for a quick observation?”

“Want to try something slightly different?”

“Should we stick with this, or pivot?”

These still do the core work of consent. They preserve choice and signal respect—without turning consent into a formal procedure.

The full Consent Burger is especially useful at moments of transition. Micro-consents are what help consent stay alive within the work you’re already doing together.

If consent is starting to feel repetitive, this is often the adjustment that helps: less structure, more responsiveness.

So, Do You Need to Ask for Consent Every Time You Introduce Something New?

No—not if consent is already present in the relationship and the work you’re doing together.

That said, it’s almost always helpful to use at least one clear, three-part consent moment within a coaching session—especially early in your work with a student, when you’re still building trust and shared norms around learning together.

And yes—asking for consent becomes especially important when what you’re about to introduce is new, emotionally vulnerable, or likely to shift how a student understands themselves or their learning.

There isn’t a perfect number of times to ask for consent. What matters is noticing readiness and staying oriented toward learning with students rather than at them.

Consent isn’t a script. It’s an attunement practice.

Want to Learn How to Use the Consent Burger in Real Sessions?

If this conversation is sparking questions about how to introduce the Consent Burger with actual students—without it feeling awkward or overdone—we have a place for that.

Inside our free Visitor’s Center, you’ll find a short course where I walk through exactly how to introduce the Consent Burger, how to adapt it for different ages, and how to use it flexibly rather than mechanically.

And if you want to keep refining tools like this alongside thoughtful educators, you’re always welcome to join the Anti-Boring Learning Lab. That’s where questions like this one come from, and where they get explored in community.